|

The Mysterious Mr. de Mohrenschildt

October 14, 2013

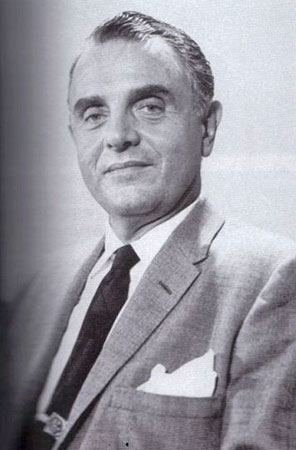

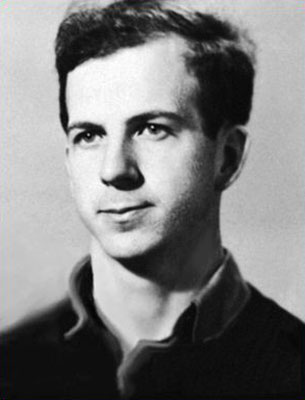

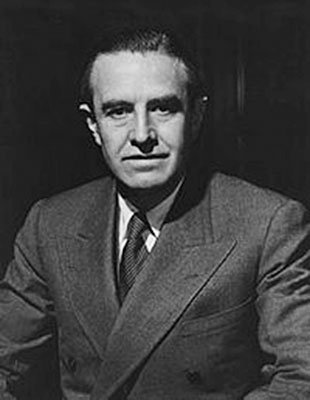

George de Mohrenschildt

"Must have angered a lot of people" In 1976, more than a decade after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, a letter arrived at the CIA, addressed to its director, the Hon. George Bush.

The letter was from a desperate-sounding man in

Dallas, who spoke regretfully of having been indiscreet in talking about Lee

Harvey Oswald and begged Poppy for help:

The writer signed himself "G. de Mohrenschildt."

by Edvard Munch

The CIA staff assumed the letter writer to be a crank.

Just to be sure, however, they asked their boss:

Bush responded by memo, seemingly self-typed:

Not recall? Once again, Poppy Bush was having

memory problems. And not about trivial matters.

George de Mohrenschildt was not just the

uncle of a roommate, but a longtime personal associate. Yet Poppy could not

recall - or more precisely, claimed not to recall - the nature of de

Mohrenschildt’s relationship with the man believed to have assassinated the

thirty-fifth president.

This would have been an unusual lapse on anyone’s part. But for the head of an American spy agency to exhibit such a blasé attitude, in such an important matter, was over the edge.

At that very moment, several federal

investigations were looking into CIA abuses - including the agency’s role in

assassinations of foreign leaders. These investigations were heading toward

what would become a reopened inquiry into Kennedy’s death.

Could it be that the lapse was not casual, and

the acknowledgment of a distant relationship was a way to forestall inquiry

into a closer one?

Writing back to his old friend, Poppy assured the Mohrenschildt that his fears were entirely unfounded. Yet half a year later, de Mohrenschildt was dead. The cause was officially determined to be suicide with a shotgun. Investigators combing through de Mohrenschildt’s effects came upon his tattered address book, largely full of entries made in the 1950’s.

Among them, though apparently eliciting no

further inquiries on the part of the police, was an old entry for the

current CIA director, with the Midland address where he had lived in the

early days of Zapata:

De Mohrenschildt and the

Oswalds

When Poppy told his staff that his old friend de Mohrenschildt "knew Oswald," that was an understatement. From 1962 through the spring of 1963, de Mohrenschildt was by far the principal influence on Oswald, the older man who guided every step of his life.

De Mohrenschildt had helped Oswald find jobs and

apartments, had taken him to meetings and social gatherings, and generally

had assisted with the most minute aspects of life for Lee Oswald, his

Russian wife, Marina, and their baby.

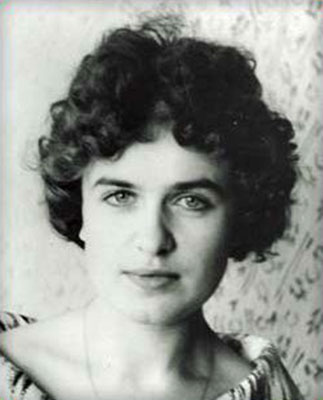

Lee Harvey Oswald, 1961  Marina Oswald De Mohrenschildt’s relationship with Oswald has tantalized and perplexed investigators and researchers for decades.

In 1964, de Mohrenschildt and his wife Jeanne

testified to the Warren Commission, which spent more time with them than any

other witness - possibly excepting Oswald’s widow, Marina.

The Commission, though, focused on George de

Mohrenschildt as a colorful, if eccentric, character, steering away every

time de Mohrenschildt recounted yet another name from a staggering list of

influential friends and associates. In the end, the commission simply

concluded in its final report that these must all be coincidences and

nothing more.

The de Mohrenschildts, the Commission said,

apparently had nothing to do with the assassination.

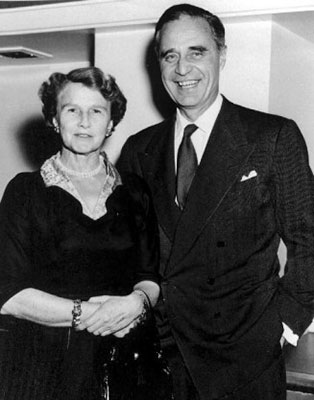

George and Jeanne de

Mohrenschildt

Even the Warren Commission counsel who questioned George de Mohrenschildt appeared to acknowledge that the Russian émigré was what might euphemistically be called an "international businessman."

For most of his adult life, de Mohrenschildt had

traveled the world ostensibly seeking business opportunities involving a

variety of natural resources - some, such as oil and uranium, of great

strategic value.

The timing of his overseas ventures was

remarkable. Invariably, when he was passing through town, a covert or even

overt operation appeared to be unfolding - an invasion, a coup, that sort of

thing.

For example, in 1961, as exiled Cubans and their

CIA support team prepared for

the Bay of Pigs invasion in Guatemala,

George de Mohrenschildt and his wife passed through Guatemala City on what

they told friends was a month-long walking tour of the Central American

isthmus.

On another occasion, the de Mohrenschildts

appeared in Mexico on oil business just as a Soviet leader arrived on a

similar mission - and even happened to meet the Communist official. In a

third instance, they landed in Haiti shortly before an unsuccessful coup

against its president that had U.S. fingerprints on it.

A Russian-born society figure was a friend both of the family of President Kennedy and his assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.

A series of strange coincidences providing the

only known link between the two families before Oswald fired the shot

killing Mr. Kennedy in Dallas a year ago was described in testimony before

The Warren Commission by George S. de Mohrenschildt.

He was actually much more intriguing - and mystifying.

As Norman Mailer noted in his book

Oswald’s Tale, de Mohrenschildt possessed,

A Name Never Dropped

During all these examinations, and notwithstanding de Mohrenschildt’s offhand recitation of scores of friends and colleagues, obscure and recognizable, he scrupulously never mentioned that he knew Poppy Bush.

Nor did investigators uncover the fact that in

the spring of 1963, immediately after his final communication with Oswald,

de Mohrenschildt had traveled to New York and Washington for meetings with

CIA and military intelligence officials.

He even had met with a top aide to Vice

President Johnson. And the commission certainly did not learn that one

meeting in New York included Thomas Devine, then Bush’s business colleague

in Zapata Offshore, who was doing double duty for the CIA.

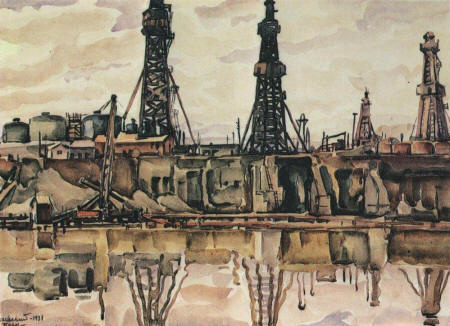

Had the Warren Commission’s investigators comprehensively explored the matter, they would have found a phenomenal and baroque back-story that contextualizes de Mohrenschildt within the extended petroleum-intelligence orbit in which the Bushes operated. Getting America Into World War I The de Mohrenschildts were major players in the global oil business since the beginning of the twentieth century, and their paths crossed with the Rockefellers and other key pillars of the petroleum establishment.

George de Mohrenschildt’s uncle and father ran

the Swedish Nobel Brothers Oil Company’s operations

in Baku, in Russian Azerbaijan on the

southwestern coast of the Caspian Sea.

This was no small matter. In the early days of

the twentieth century, the region held roughly half of the world’s known oil

supply. By the start of World War I, every major oil interest in the world,

including the Rockefellers’ Standard Oil, was scrambling for a piece of

Baku’s treasure or intriguing to suppress its competitive potential. (Today,

ninety years later, they are at it again.)

In 1915, the czar’s government dispatched a second uncle of George de Mohrenschildt, the handsome young diplomat Ferdinand von Mohrenschildt, to Washington to plead for American intervention in the war - an intervention that might rescue the czarist forces then being crushed by the invading German army.

President Woodrow Wilson had been

reelected partly on the basis of having kept America out of the war.

But as with all leaders, he was surrounded by

men with their own agendas. A relatively close-knit group embodying the

nexus of private capital and intelligence-gathering inhabited the highest

levels of the Wilson administration.

Secretary of State Robert Lansing was the

uncle of a diplomat-spy by the name of Allen Dulles.

Wilson’s closest adviser, "Colonel" Edward

House, was a Texan and an ally of the ancestors of James A. Baker III,

who would become Poppy Bush’s top lieutenant. Czarist Russia then owed fifty

million dollars to a Rockefeller-headed syndicate.

Keeping an eye on such matters was the U.S.

ambassador to Russia, a close friend of George Herbert Walker’s from St.

Louis.

Allen Dulles

during WW I

Once the United States did enter the war, Prescott Bush’s father, Samuel Bush, was put in charge of small arms production.

The Percy Rockefeller-headed Remington Arms

Company got the lion’s share of the U.S. contracts. It sold millions of

dollars worth of rifles to czarist forces, while it also profited handsomely

from deals with the Germans.

In 1917, Ferdinand von Mohrenschildt’s mission to bring America into the world war was successful on a number of levels. Newspaper clippings of the time show him to be an instant hit on the Newport, Rhode Island, millionaires’ circuit. He was often in the company of Mrs. J. Borden Harriman, of the family then befriending Prescott Bush and about to hire Prescott’s future father-in-law, George Herbert Walker.

Not long after that, Ferdinand married the

step-granddaughter of President Woodrow Wilson.

Prescott Bush  Prescott Bush,

Dorothy Walker Bush

In quick succession, the United States entered World War I, and the newlywed Ferdinand unexpectedly died.

The von Mohrenschildt family fled Russia along

with the rest of the aristocracy. Emanuel Nobel sold half of the Baku

holdings to Standard Oil of New Jersey, with John D. Rockefeller Jr.

personally authorizing the payment of $11.5 million.

Over the next couple of decades, members of the

defeated White Russian movement, which opposed the Bolsheviks and fought the

Red Army from the 1917 October Revolution until 1923, would find shelter in

the United States, a country that shared the anti-Communist movement’s

ideological sentiments.

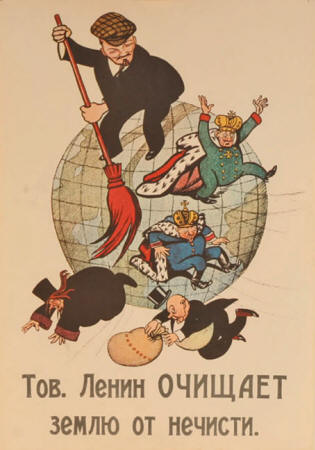

What the von Mohrenschildts

escaped.

Bush and de Mohrenschildt Families - Deeply Intertwined In 1920, Ferdinand’s nephew Dimitri von Mohrenschildt, the older brother of George, arrived in the United States and entered Yale University.

His admission was likely smoothed by the

connections of the Harriman family, which soon persuaded the Bolshevik

Russian government to allow them to reactivate the Baku oilfields.

At that point, the Harriman operation was being

directed by the brilliant international moneyman George Herbert Walker, the

grandfather of Poppy Bush.

Baku Oil Rigs

by Konstantin Bogaevsky

The Soviets had expropriated the assets of the Russian ruling class, not least the oil fields.

Though ultimately willing to cooperate with some

Western companies, the Communists had created an army of angry White Russian

opponents, who vowed to exact revenge and regain their holdings. This group,

trading on an American fascination with titles, was soon ensconced in (and

often intermarried with) the East Coast establishment.

The New York newspapers of the day were full of

reports of dinners and teas hosted by Prince This and Count That at

the top of Manhattan hotels.

Dimitri von Mohrenschildt plunged into this milieu. After graduating from Yale, he was offered a position teaching the young scions of the new oil aristocracy at the exclusive Loomis School near Hartford, Connecticut, where John D. Rockefeller III was a student (and his brother Winthrop soon would be).

There, Dimitri became friendly with Roland

and Winifred "Betty" Cartwright Holhan Hooker, who were

prominent local citizens.

Roland Hooker was enormously well connected; his

father had been the mayor of Hartford, his family members were close friends

of the Bouviers (Jackie Kennedy’s father’s family), and his sister was

married to Prince Melikov, a former officer in the Imperial Russian Army.

While Dimitri von Mohrenschildt clearly enjoyed the high-society glamour, in reality his life was heading underground.

Dimitri’s lengthy covert résumé would include

serving in the Office of Strategic Services wartime spy agency and later

cofounding Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. In 1941, Dimitri also

founded a magazine, the Russian Review, and later became a professor at

Dartmouth.

When the Hooker marriage unraveled, Dimitri began seeing Betty Hooker. In the summer of 1936, immigration records show that Dimitri traveled to Europe, followed a week later by Betty Hooker with her young daughter and adolescent son. Betty’s son, Edward Gordon Hooker, entered prep school at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

There, he shared a small cottage with George H.

W. "Poppy" Bush. Bush and Hooker became inseparable. They worked together on

Pot Pourri, the student yearbook, whose photos show a handsome young Poppy

Bush and an even more handsome Hooker.

The friendship would continue in 1942, when both

Bush and Hooker, barely eighteen, enlisted in the Navy and served as pilots

in the Pacific. Afterward, they would be together at Yale. When Hooker

married, Poppy Bush served as an usher.

The relationship between Bush and Hooker lasted

for three decades, until 1967, when Hooker died of an apparent heart attack.

He was just forty-three.

Six years after Hooker’s death, Poppy Bush would

serve as surrogate father, giving away Hooker’s daughter at her wedding to

Ames Braga, scion of a Castro-expropriated Cuban sugar dynasty.

Another Careful Disconnect The relationship couldn’t have been much closer.

Yet Bush never mentions Hooker in his memoirs or

published recollections, even though he finds room for scores of more

marginal figures. Certainly his family was aware of Hooker.

Poppy’s prep school living arrangements would have mattered to Prescott Bush. The Bush clan is famously gregarious, and like many wealthy families, it puts great stock in the establishment of social networks that translate into influence and advantage. Prescott took a strong interest in meeting his children’s friends and the friends’ parents, as expressed in family correspondence and memoirs.

Moreover, as a prominent Connecticut family with

deep colonial roots, the Hookers would have had great appeal for Prescott

Bush, an up-and-coming Connecticut resident with political aspirations and a

great interest in the genealogy of America’s upper classes.

In 1937, Betty Hooker and Dimitri von Mohrenschildt married.

By then, Dimitri had been hired by Henry Luce as

a stringer for Time magazine. Prescott would likely have been keen to know

his son’s roommate’s stepfather - this intriguing Russian anti-Communist

aristocrat, with a background in the oil business and a degree from Yale,

working for Prescott’s

Skull and Bones friend Luce.

Meanwhile, Dimitri’s younger brother, George, had been living with their family in exile in Poland, where he finished high school and then joined a military academy and the cavalry. In May 1938, George arrived from Europe and moved in with his brother and new sister-in-law in their Park Avenue apartment.

Young George de Mohrenschildt came to America

armed with the doctoral dissertation that reflected the future trajectory of

his life: "The Economic Influence of the United States on Latin America."

The oil south of the border was certainly of

interest to Wall Street figures such as Prescott Bush and his colleagues,

who were deeply involved in financing petroleum exploration in new areas.

From Émigré to Spy The White Russian émigrés in the United States were motivated by both ideology and economics to serve as shock troops in the growing cold war conflict being managed by Prescott’s friends and associates.

No one understood this better than Allen Dulles,

the Wall Street lawyer, diplomat, and spy-master-in ascension.

Even in the period between the two world wars,

Dulles was already molding Russian émigrés into intelligence operatives. He

moved back and forth between government service and Wall Street lawyering

with the firm Sullivan and Cromwell, whose clients included United Fruit and

Brown Brothers Harriman.

The latter was at that time led by Averell and

Roland Harriman and Prescott Bush.

W. Averell Harriman

Whether in government or out, Dulles’s interests and associates were largely the same.

He seemed to enjoy the clandestine work more

than the legal work.

As Peter Grose notes in Gentleman Spy:

The Life of Allen Dulles, he worked during the 1940 presidential

campaign to bring Russian, Polish, and Czechoslovak émigrés into the

Republican camp.

Dimitri von Mohrenschildt was a star player in

this game on a somewhat exalted level.

He found sponsorship for a role as an academic

and publisher specializing in anti-Bolshevik materials, and later became

involved in more ambitious propaganda work with Radio Liberty and Radio Free

Europe.

Younger brother George was more willing to get

his hands dirty.

He took a job in the New York office of a French

perfume company called Chevalier Garde, named for the Czar’s most elite

troops, the Imperial Horse Guards. His bosses were powerful czarist Russian

émigrés, well connected at the highest levels of Manhattan society, who

worked during World War II in army intelligence and the OSS.

One of them, Prince Serge Obolensky, had

escaped Soviet Russia after a year of hiding and became a much-married New

York society figure whose wives included Alice Astor.

His brother-in-law Vincent Astor was secretly

asked by FDR in 1940 to set up civilian espionage offices in Manhattan at

Rockefeller Center.

Astor was soon joined in this effort by Allen

Dulles.

and Jacqueline Kennedy

Onassis

1975

The next stop for George de Mohrenschildt was a home furnishings company.

His boss there was a high-ranking French

intelligence official, and together they monitored and blocked attempts by

the Axis war machine to procure badly needed petroleum supplies in the

Americas.

Young de Mohrenschildt then traveled to the

southwest, where he exhibited still more impressive connections.

Ostensibly there to work on oil derricks, he

landed a meeting with the chairman of the board of Humble Oil, the Texas

subsidiary of Standard Oil of New Jersey, predecessor to Exxon.

Prince Serge Obolensky

circa 1943

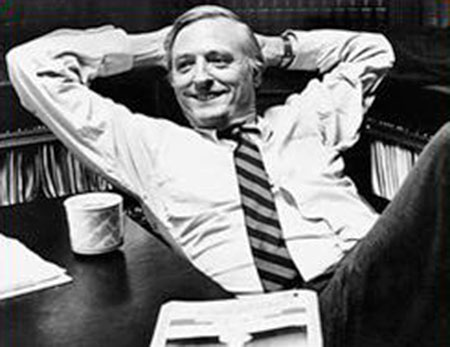

The jobs kept becoming more interesting. By the midforties, de Mohrenschildt was working in Venezuela for Pantepec Oil, the firm of William F. Buckley’s family.

Pantepec later had abundant connections with the

newly created CIA and was deeply involved in foreign intrigue for decades.

The Buckley boys, like the Bushes, had been

in Skull and Bones, and Bill Buckley,

whose conservative intellectual magazine National Review was often

politically helpful to Poppy Bush, would in later years admit to a stint

working for the CIA himself.

William F. Buckley, Jr.

George de Mohrenschildt’s foreign trips - and some of his domestic wanderings as well - drew the interest of various American law enforcement agencies.

These incidents appear to have been deliberate

provocations, such as his working on "sketches" outside a U.S. Coast Guard

station. In many of these cases de Mohrenschildt would be briefly questioned

or investigated, the result of which was a dossier not unlike that of Lee

Harvey Oswald’s.

These files were full of declared doubts about

his loyalties and speculation at various times that he might be a Russian,

Japanese, French, or German spy. A classic opportunist, he might have been

any or all of these.

But he also could have simply been an American

spy who was creating a cover story.

|

Revealing that which is concealed. Learning about anything that resembles real freedom. A journey of self-discovery shared with the world. Have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them - Ephesians 5-11 Join me and let's follow that high road...