IMF Discusses 'One-Off' Wealth Tax

It

is undoubtedly nice to have a job with the World Bank or the IMF. One

of the most enticing aspects for those employed at these organizations

(which n.b. are entirely funded by tax payers), is no doubt that apart

from receiving generous salaries and perks, they themselves don't have

to pay any taxes. What a great gig! Since these organizations are so to

speak 'extra-territorial', they are held to be outside the grasp of

specific tax authorities.

This

doesn't keep them from thinking up various ways of how to resolve the

by now well-known problem of the looming insolvency of various

welfare/warfare states. In fact, they have quite a strong incentive to

come up with such ideas, since their own livelihood depends on the

revenue streams continuing without a hitch. One recent proposal in

particular has made waves lately (it can be found in this paper

– pdf), mainly because it sounds precisely like the kind of thing many

people expect desperate governments to resort to when push comes to

shove, not least because they have taken similar measures repeatedly

throughout history.

The

recent depositor haircut in Cyprus has also contributed to such

expectations becoming more widespread. We believe is that it is far

better to let shareholders, bondholders and depositors (in that order)

take their lumps in the event of bank insolvencies rather than forcing

the bill on unsuspecting tax payers via bailouts. What was odious about

the Cypriot haircut was mainly that the government steadfastly lied to

its citizens about what was coming and that certain classes of

depositors, such as e.g. the president's relatives, got all their money

out just a week or two prior to the bank holiday, by what we are assured

was sheer coincidence (this unexpected twist of fate which proved so

fortuitous to the president's clan increased the costs for remaining

depositors).

Still,

the entire escapade was a salutary event in many respects. It proved

that government bonds are not a reliable store of value (it was mainly

their holdings of Greek government bonds that got the Cypriot banks into

hot water) and it was a reminder that fractionally reserved banks are

inherently insolvent. In short, it has helped a bit to concentrate the

minds of many of those who still remain whole and has sensitized them to

other attempts of grabbing private wealth that may be coming down the

pike.

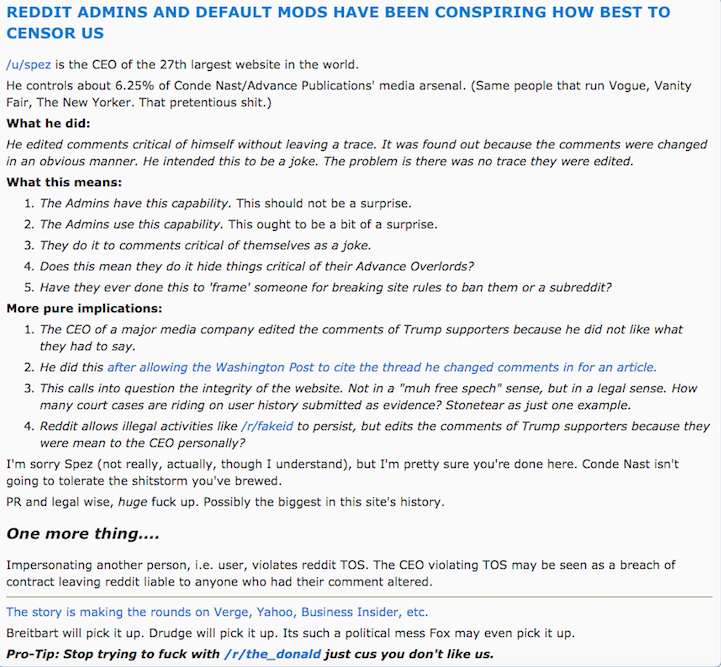

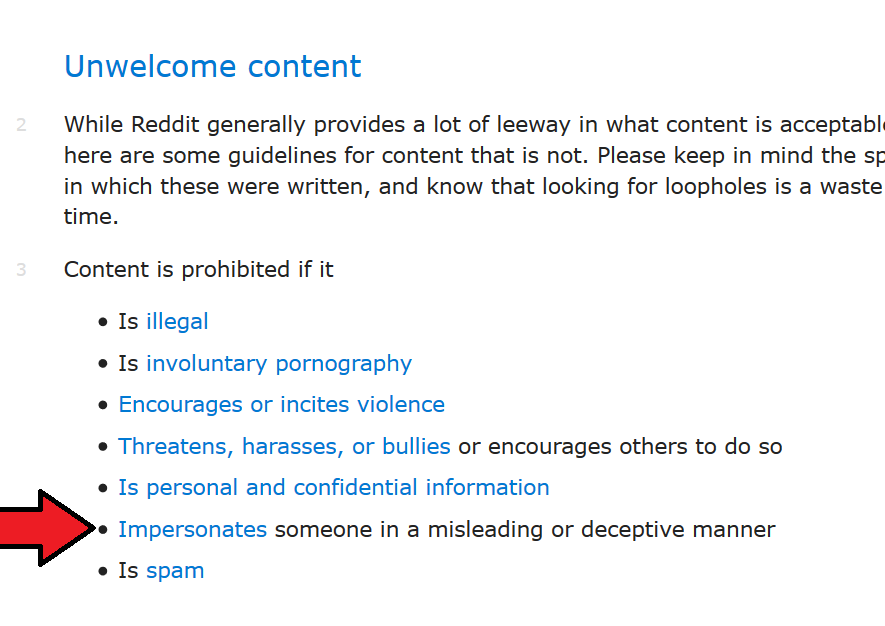

This

is probably also the reason why a paragraph in an IMF document that may

otherwise not have received much scrutiny as it would have been

considered too outlandish an idea, has created quite a stir. That such

proposals are made from the comfortable environment of a tax free zone

is quite ironic. Here is the paragraph in question:

“The

sharp deterioration of the public finances in many countries has

revived interest in a “capital levy”— a one-off tax on private

wealth—as an exceptional measure to restore debt sustainability. The

appeal is that such a tax, if it is implemented before avoidance is

possible and there is a belief that it will never be repeated, does not

distort behavior (and may be seen by some as fair). There have been illustrious supporters, including Pigou, Ricardo, Schumpeter, and—until he changed his mind—Keynes. The

conditions for success are strong, but also need to be weighed against

the risks of the alternatives, which include repudiating public debt

or inflating it away (these, in turn, are a particular form of wealth

tax—on bondholders—that also falls on nonresidents).

There is a surprisingly large amount of experience to draw on,

as such levies were widely adopted in Europe after World War I and in

Germany and Japan after World War II. Reviewed in Eichengreen (1990),

this experience suggests that more notable than any loss of credibility

was a simple failure to achieve debt reduction, largely because the

delay in introduction gave space for extensive avoidance and capital

flight—in turn spurring inflation.

The

tax rates needed to bring down public debt to precrisis levels,

moreover, are sizable: reducing debt ratios to end-2007 levels would

require (for a sample of 15 euro area countries) a tax rate of about 10

percent on households with positive net wealth.”

(emphasis added)

It

is actually not a surprise that there is a 'wealth of experience to

draw on'. Throughout history, governments have thought up all sorts of

methods to get their hands on their subjects' wealth. It would have only

been a surprise if there had been no 'experiences to draw on'. In fact,

as wasteful and inefficient as the State is otherwise, this is one of

the tasks in which it proves extremely resourceful, inventive and

efficient. The extraction of citizens' wealth is an activity at which it

excels.

Apparently the IMF judges that stealing 10% of all private wealth in one fell swoop is perfectly fine as long as 'some see it as fair'.

Some of course would. There is however a crucial difference between

imposing such a levy at gunpoint and letting bondholders take losses.

The latter have taken the risk of not getting repaid voluntarily. No-one forced them to buy government bonds.

As

to the pseudo-consolation that such a confiscation should be presented

as a 'one off' event so as 'not to distort behavior', let's be serious.

The moment governments gets more loot in, they will start spending it

with both hands and in no time at all will find themselves back at

square one.

States and Taxation

As

Franz Oppenheimer has pointed out, States are essentially the result of

conquests by gangs of marauders who realized that operating a

protection racket was far more profitable than simply grabbing

everything that wasn't nailed down and making off with. In modern

democracies it has become easier for citizens to join the ruling class

(i.e., the more civilized version of these marauders), which has greatly

increased acceptance of the State. Also, a large number of people has

been bought off with 'free' goodies and all and sundry have had it

drilled into them throughout their lives that the State is both

inevitable and irreplaceable.

There

are of course other advantages to be had in democracies, such as the

fact that a market economy is allowed to exist (even if it is severely

hampered) and that free speech is tolerated. One considerable drawback

though is that taxation has historically never been higher than in the

democratic order (and still these States are all teetering on the edge

of bankruptcy anyway).

As

an aside, conscription and the closely associated concept of 'total

war' are also democratic 'achievements'. Whereas war was once largely

confined to strictly localized battles between professionals, the French

revolution and its aftermath was a pivot point that marked a change in

thinking about war and ultimately paved the way for legitimizing the

all-encompassing atrocities of the 20th century, with civilians suddenly regarded as fair game.

A

little historical excursion: Under medieval kings there was at least

occasionally a chance that a tax might actually be repealed, even if

only temporarily. For instance, in 1012 the heregeld was

introduced in England, an annual tax first assessed by King Ethelred the

Unready (better: 'the Ill-Advised'). Its purpose was to help pay for

mercenaries to fight the invasion of England by King Sweyn Forkbeard of

Denmark.

Ethelred had been forced to pay a tribute to the Danes for many years, known as 'Danegeld'.

In 1002 AD he apparently got fed up and in a fit of pique ordered the

murder of all Danes in England, an event known as the St. Brice's Day

Massacre. Not surprisingly, this incensed the Danes and Sweyn

Forkbeard's invasion was the result. Sweyn seized the English throne in

1013, but died in 1014, upon which Ethelred was invited back by the

nobles (under the condition that he 'rule more justly'). However, he

soon died as well, which left Edmund Ironside in charge for a few months

in 1016. Sweyn's son Knut eventually conquered England later in the

same year. Knut simply continued to collect the heregeld tax after ascending to the throne. The heregeld

was a land tax based on the number of 'hides' one owned (the hide is a

medieval area measure, the precise extent of which is disputed among

historians; one hide was once thought to be equivalent to 120 acres, but

this is no longer considered certain). The tax was finally abolished

by King Edward the Confessor in 1051 (Edward was Ethelred's seventh son

and was later canonized. He was the last king of the House of Wessex).

The tax relief unfortunately proved short-lived. Shortly after Edward's

death in 1066, the Normans conquered England and 'hideage' was reintroduced.

Ethelred the Unready, inventor of the heregeld

tax, holding an oversized sword. Although he is generally referred to

as 'the Unready', this translation of his nickname is actually

incorrect: rather, it should be 'ill-advised' or 'ill-prepared'. In the

original old English “Æþelræd Unræd”, the term 'unread' is

actually a pun on his name. 'Ethelred' means 'noble counsel' (in

modern German: 'Edler Rat') – his nickname thus juxtaposes 'noble

counsel' with 'no counsel' or 'evil counsel'.

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ethelred's nemesis, the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard, likewise holding an oversized sword

Ethelred's nemesis, the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard, likewise holding an oversized sword

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

The man who abolished the heregeld tax, St. Edward the Confessor. It is noteworthy that he is usually not

depicted holding an oversized sword (he was however reportedly not

inexperienced in military matters. When Welsh raiders attacked English

lands in 1049, they soon had reason for regret. The head of one of their

leaders, Rhys ap Rhydderch, was delivered to Edward in 1052. The head

was no longer attached to the rest of Rhys). Edward is probably not

mainly remembered for this, but he gave England fifteen glorious years

free of hideage tax.

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

As

Murray Rothbard writes in 'The Ethics of Liberty' on the State's

monopoly of force and its power to extract revenue by coercion:

“But,

above all, the crucial monopoly is the State’s control of the use of

violence: of the police and armed services, and of the courts—the locus

of ultimate decision-making power in disputes over crimes and contracts.

Control of the police and the army is particularly important in

enforcing and assuring all of the State’s other powers, including the

all-important power to extract its revenue by coercion.

For there is one crucially important power inherent in the nature of the State apparatus. All other persons

and groups in society (except for acknowledged and sporadic criminals

such as thieves and bank robbers) obtain their income voluntarily: either by

selling goods and services to the consuming public, or by voluntary

gift (e.g., membership in a club or association, bequest, or

inheritance). Only the State obtains its revenue by coercion,

by threatening dire penalties should the income not be forthcoming. That

coercion is known as “taxation,” although in less regularized epochs it

was often known as “tribute.” Taxation is theft, purely and simply even

though it is theft on a grand and colossal scale which no acknowledged

criminals could hope to match. It is a compulsory seizure of the

property of the State’s inhabitants, or subjects.

It would be an instructive exercise for the skeptical reader to try to frame a definition of taxation which does not also include

theft. Like the robber, the State demands money at the equivalent of

gunpoint; if the taxpayer refuses to pay his assets are seized by force,

and if he should resist such depredation, he will be arrested or shot

if he should continue to resist. It is true that State apologists

maintain that taxation is “really” voluntary; one simple but instructive

refutation of this claim is to ponder what would happen if the

government were to abolish taxation, and to confine itself to simple

requests for voluntary contributions. Does anyone really believe

that anything comparable to the current vast revenues of the State

would continue to pour into its coffers? It is likely that even those

theorists who claim that punishment never deters action would balk at

such a claim. The great economist Joseph Schumpeter was correct when he

acidly wrote that “the theory which construes taxes on the analogy of

club dues or of the purchase of the services of, say, a doctor only

proves how far removed this part of the social sciences is from

scientific habits of mind.”

(emphasis in original)

In

the pages following this excerpt, Rothbard expertly demolishes numerous

spurious arguments that have been forwarded in support of taxes by

people claiming that they are somehow akin to voluntary contributions.

The Vote Changes Nothing

In

the course of this disquisition Rothbard also discusses whether the

democratic vote actually makes a difference in this context, whether, as

he puts it, the “act of voting makes the government and all its works and powers truly “voluntary.”

On this topic he quotes from the observations of anarchist political

philosopher Lysander Spooner, who wrote the following in 'No Treason:The Constitution of No Authority':

“In

truth, in the case of individuals their actual voting is not to be

taken as proof of consent. . . . On the contrary, it is to be considered

that, without his consent having even been asked a man finds himself

environed by a government that he cannot resist; a government that

forces him to pay money renders service, and foregoes the exercise of

many of his natural rights, under peril of weighty punishments.

He

sees, too, that other men practice this tyranny over him by the use of

the ballot. He sees further, that, if he will but use the ballot

himself, he has some chance of relieving himself from this tyranny of

others, by subjecting them to his own. In short, he finds himself,

without his consent, so situated that, if he uses the ballot, he may

become a master, if he does not use it, he must become a slave.

(emphasis added)

Discussing

taxation in the same text, Spooner famously compares government to

highwaymen. He is however not merely equating one with the other, but

rather concludes that highwaymen are to be preferred. After all, neither

are their activities attended by hypocrisy, nor are their demands

without limit (we would add to this that no-one ever published learned

papers advising them how to best go about grabbing more loot).

“It

is true that the theory of our Constitution is, that all taxes are paid

voluntarily; that our government is a mutual insurance company,

voluntarily entered into by the people with each other. . . .

But

this theory of our government is wholly different from the practical

fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man:

“Your money, or your life.” And many, if not most, taxes are paid under

the compulsion of that threat.

The

government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring

upon him from the roadside, and, holding a pistol to his head, proceed

to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that

account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.

The

highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and

crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim

to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He

does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired

impudence enough to profess to be merely a “protector,” and that he

takes men’s money against their will, merely to enable him to “protect”

those infatuated travelers, who feel perfectly able to protect

themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection.

He

is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore,

having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does

not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to

be your rightful “sovereign,” on account of the “protection” he affords

you. He does not keep “protecting” you, by commanding you to bow down

and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do

that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his

interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a

traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without

mercy if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too

much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and

villainies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you,

attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.”

(emphasis added)

Somehow we don't think that Mr. Spooner would have been a very big fan of the IMF and its ideas.

Lysander Spooner had their number.

Lysander Spooner had their number.

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Conclusion:

The particular wealth tax proposal mentioned by the IMF en passant is odious in the extreme, especially as the wealth to be taxed has already been taxed at what are historically stratospheric rates.

It

is noteworthy that the alternatives discussed by the IMF for heavily

indebted states which are weighed down by the wasteful spending of

yesterday appear to have been reduced to 'default' (either outright or

via hyperinflation) or 'more confiscation'. How about rigorously cutting

spending instead?

One

must also keep in mind that any proposals concerning so-called 'tax

fairness' are in the main about 'how can we get our hands on wealth that

currently still eludes us'. People need to be aware that worsening the

situation of one class of tax payers is never going to improve the

situation of another. The IMF's publication is a case in point: in all

its yammering about 'tax fairness', the possibility of lowering anyone's

taxes is not mentioned once (not to mention that it seems quite

hypocritical for people who are exempted from taxes to go on about

imposing 'tax fairness' on others).

Lastly, a popular as well as populist target of the self-appointed arbiters of 'fairness' are loopholes, but as we have previously discussed, they are to paraphrase Mises 'what allows capitalism to breathe'.

Closing them will in the end only lead to higher costs for consumers,

less innovation, lower growth and considerable damage to retirement

savings.

Two apposite statues at Trago Mills, UK, dedicated to HM Inland Revenue – Loot & Extortion.